By Brook Larmer

Originally printed in the National Geographic Magazine - May, 2008

Not a drop of rain has fallen in months, and the only cloudscome from sandstorms lashing across the desert. But as the Yellow River bendsthrough the barren landscape of north-central China, a startling visionshimmers on the horizon: emerald green rice fields, acres of yellow sunflowers,lush tracts of corn, wheat, and wolfberry—all flourishing under a mercilesssky.

This is no mirage. The vast oasis in northern Ningxia, nearthe midpoint of the Yellow River's 3,400-mile journey from the Plateau of Tibetto the Bo Hai sea, has survived for more than 2,000 years, ever since the Qinemperor dispatched an army of peasant engineers to build canals and grow cropsfor soldiers manning the Great Wall. Shen Xuexiang is trying to carry on thattradition today. Lured here three decades ago by the seemingly limitless supplyof water, the 55-year-old farmer cultivates cornfields that lie between theruins of the Great Wall and the silt-laden waters of the Yellow River. From thebank of an irrigation canal, Shen gazes over the green expanse and marvels atthe river's power: "I always thought this was the most beautiful placeunder heaven." But this earthly paradise is disappearing fast. Theproliferation of factories, farms, and cities—all products of China'sspectacular economic boomis sucking the Yellow River dry. What water remains isbeing poisoned. From the canal bank, Shen points to another surreal flash ofcolor: blood-red chemical waste gushing from a drainage pipe, turning the watera garish purple. This canal, which empties into the Yellow River, once teemedwith fish and turtles, he says. Now its water is too toxic to use even forirrigation; two of Shen's goats died within hours of drinking from the canal.

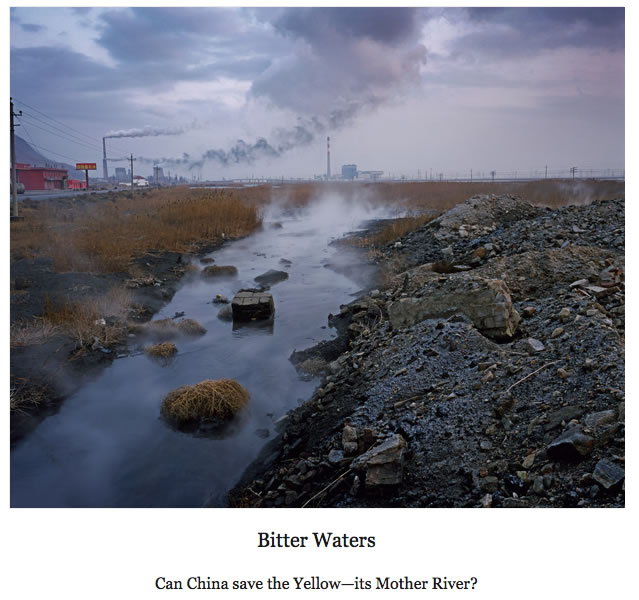

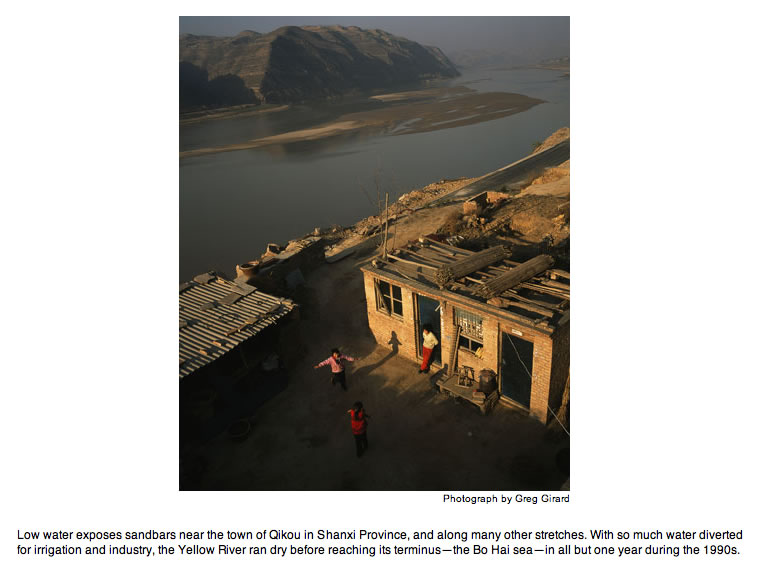

Few waterways capture the soul of a nation more deeply thanthe Yellow, or the Huang, as it's known in China. It is to China what the Nileis to Egypt: the cradle of civilization, a symbol of enduring glory, a force ofnature both feared and revered. From its mystical source in the 14,000-footTibetan highlands, the river sweeps across the northern plains where China'soriginal inhabitants first learned to till and irrigate, to make porcelain andgunpowder, to build and bury imperial dynasties. But today, what the Chinesecall the Mother River is dying. Stained with pollution, tainted with sewage,crowded with ill-conceived dams, it dwindles at its mouth to a lifelesstrickle. There were many days during the 1990s that the river failed to reachthe sea at all.

The demise of the legendary river is a tragedy whoseconsequences extend far beyond the more than 150 million people it sustains.The Yellow's plight also illuminates the dark side of China's economic miracle,an environmental crisis that has led to a shortage of the one resource no nationcan live without: water.

If that sounds like hyperbole, consider what is happeningalready in the Yellow River Basin. The spread of deserts is creating a dustbowl that may dwarf that of the American West in the 1930s, driving down grainproduction and pushing millions of "environmental refugees" off theland. The poisonous toxins choking the waterways—50 percent of the Yellow Riveris considered biologically dead—have led to a spike in cases of cancer, birthdefects, and waterborne disease along their banks. Pollution-related protestshave jumped—there were 51,000 across China in 2005 alone—and could metastasizeinto social unrest. Any one of these symptoms, if unchecked, could hinderChina's growth and reverberate across world markets. Taken together, thelong-term impact could be even more devastating. As Premier Wen Jiabao has putit, the shortage of clean water threatens "the survival of the Chinesenation."

The Yellow River's epic journey across northern China is aprism through which to see the country's unfolding water crisis. From theTibetan nomads leaving their ancestral lands near the river's source to the "cancer villages" languishing in silence near the delta, the MotherRiver puts a human face on the costs of environmental destruction. But it alsoshows how this emergency is shocking the government—and a small cadre ofenvironmental activists—into action. The fate of the Yellow River still hangsin the balance.

Sitting on a ridge nearly three miles above sea level, arosy-cheeked Tibetan herder with two gold teeth looks out over the highlandsher family has roamed for generations. It is a scene of stark beauty: rollinghills blanketed by sprouts of summer grass; herds of yaks and sheep grazing ondistant slopes; and in the foreground a clear, shallow stream that is thebeginning of the Yellow River. "This is sacred land," says the woman,a 39-year-old mother of four named Erla Zhuoma, recalling how her family ofnomads would rotate through here to graze their 600 sheep and 150 yaks. Nolonger, she says, shaking her head in dismay. "The drought has changedeverything."

The first signs of trouble emerged several years ago, whenthe region's lakes and rivers began drying up and grasslands started witheringaway, turning the search for her animals' food and water into marathonexpeditions. Chinese scientists say the drought is a symptom of global warmingand overgrazing. But Zhuoma blames the misfortune on outsiders—members of theethnic Han Chinese majority—who angered the gods by mining for gold in a holymountain nearby and fishing in the sacred lakes at the Yellow River's source.How else could she comprehend the death by starvation of more than half of heranimals? Fearing further losses, Zhuoma and her husband accepted a governmentoffer to sell off the rest in exchange for a thousand-dollar annual stipend anda concrete-block house in a resettlement camp near the town of Madoi. Theherders are now the herded, nomads with nowhere to go.

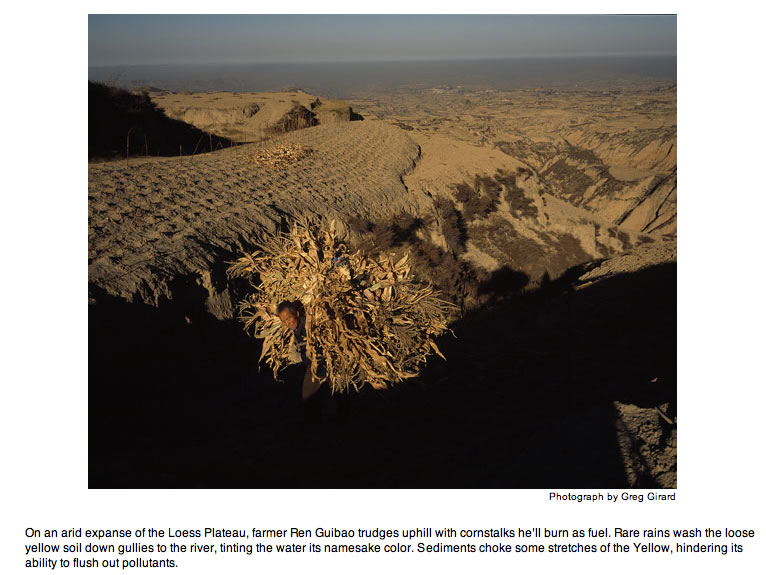

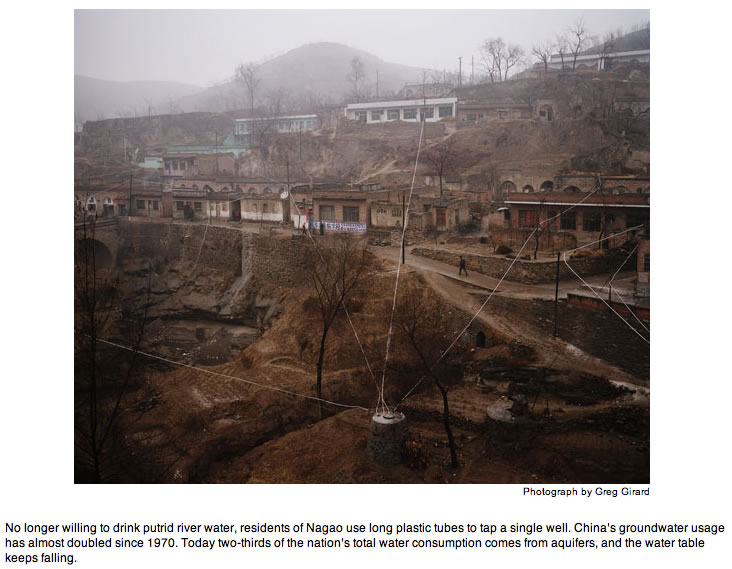

China's water crisis begins on the roof of the world, wherethe country's three renowned rivers (the Yellow, the Yangtze, and the Mekong)originate. The glaciers and vast underground springs of the Qinghai-Tibetplateau—known as China's "water tower"—supply nearly 50 percent ofthe Yellow River's volume. But a hotter, drier climate is sending the delicateecosystem into shock. Average temperatures in the region are increasing,according to the Chinese weather bureau, and could rise as much as three tofive degrees Celsius by the end of the century. Already, more than 3,000 of the4,077 lakes in Qinghai Province's Madoi County have disappeared, and the dunesof the high desert lap menacingly at those that remain. The glaciers,meanwhile, are shrinking at a rate of 7 percent a year. Melting ice may addwater to the river in the short term, but scientists say the long-termconsequences could be fatal to the Yellow.

To save its great rivers, Beijing is performing a sort oftechnological rain dance, with the most ambitious cloud-seeding program in theworld. During summer months, artillery and planes bombard the clouds above theYellow River's source area with silver iodide crystals, around which moisturecan collect and become heavy enough to fall as rain. In Madoi, where the thunderousexplosions keep Zhuoma's family awake at night, the meteorologists staffing theweather station say the "big gun" project is increasing rainfall andhelping replenish glaciers near the Yellow River's source. Local Tibetans,however, believe the rockets, by angering the gods once more, are perpetuatingthe drought. Like thousands of resettled Tibetan refugees across Qinghai,Zhuoma mourns the end of an ancient way of life. The family's wealth, oncemeasured by the size of its herds, has dwindled to the few adornments shewears: three silver rings, a stone necklace, and her two gold teeth. Zhuoma hasno job, and her husband, who rents a tractor to make local deliveries, earnsthree dollars on a good day. Not long ago the family ate meat every day; now theyget by on noodles and fried dough. "We have no choice but to adjust,"she says. "What else can we do?" From her concrete home, Zhuoma canstill see the silvery beginnings of the Yellow River, but her relationship tothe water and the land—to her heritage—has been lost forever.

"What are you doing?" the security guard demands."Nothing," replies the stocky woman lurking outside the gates of thepaper mill, tucking her secret weapon—a handheld global positioningdevice—under her sweater. The guard eyes her for a minute, and the woman, a51-year-old laid-off factory worker named Jiang Lin, holds her breath. When heturns away, she pulls out the GPS and quickly locks in the paper mill'scoordinates.

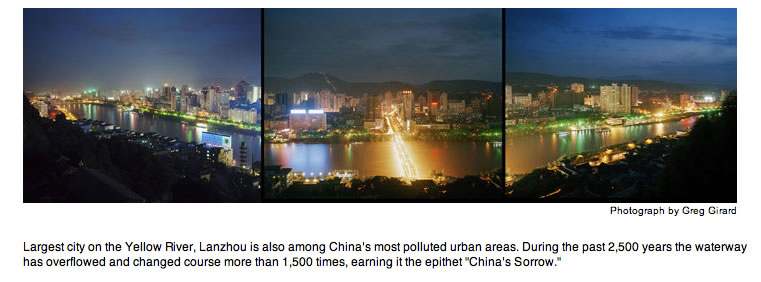

As an employee of Green Camel Bell, an environmental groupin the western city of Lanzhou, Jiang is following up on a tip that the mill isdumping untreated chemical waste into a tributary of the Yellow River. Thereare hundreds of such factories around Lanzhou, a former Silk Road trading postthat has morphed into a petrochemical hub. In 2006 three industrial spills heremade the Yellow River run red. Another turned it white. This one is taintingthe tributary a toxic shade of maroon. When Jiang gets back to the office, theGPS data will be emailed to Beijing and uploaded onto a Web-based "pollution map" for the whole world to see.

For all of Lanzhou's pride in being the first and biggestcity along the Yellow River, it is better known for its massive discharge ofindustrial and human waste. But even here there is a glimmer of hope: the firstseedlings of environmental activism, which may be the only chance for theriver's salvation. In the mid-1990s a mere handful of environmental groupsexisted in China. Today there are several thousand, including Green Camel Bell.Jiang Lin's 25-year-old son, Zhao Zhong, founded the group in 2004 to helpclean up the city and protect the Yellow River. With only five paid staff,Green Camel Bell is a shoestring operation kept afloat by grants from anAmerican NGO, Pacific Environment. The name they chose, after the reassuringbells worn by camels in Silk Road caravans, is meant to be "a sign oflife," says Jiang. "The bell is supposed to give hope to everyone whohears it."

At long last Beijing appears willing to listen. After threedecades blindly pursuing growth, the government is starting to grapple with theenvironmental costs. The impact is not simply monetary, though the World Bankcalculates that environmental damage robs China of 5.8 percent of its GDP eachyear. It is also social: Irate citizens last year flooded the government withhundreds of thousands of official environmental complaints. Whether to save theenvironment or stave off social unrest, Beijing has adopted ambitious goals,aiming for a 30 percent reduction in water consumption and a 10 percentdecrease in pollution discharges by 2010.

Yet despite the good intentions, the crisis is only gettingworse, reflecting Beijing's loss of control over the country's growth-hungryprovinces. Leading environmental lawyer Wang Canfa estimates that "only 10percent of environmental laws are enforced." Unable to count on its ownbureaucracy, Beijing has warily embraced the media and grassroots activists tohelp pressure local industry. But pity the ecological crusader who speaks outtoo much. He could end up like Wu Lihong, an activist who was jailed andallegedly tortured last year for publicizing the toxic algal blooms in centralChina's Tai Lake.

Back in the Green Camel Bell office, Jiang stresses thegroup's cordial relations with local authorities. "The government has beenworking hard to stop factories from dumping," she says. Nevertheless,along her office wall stand plastic bottles filled with water discharged byfactories and ranging in color from yellow to magenta—all unanalyzed for lackof funds. Even with its modest resources, Green Camel Bell has mobilizedvolunteers to help survey the ecology of the 24-mile section of the YellowRiver that flows through Lanzhou. Their most important, and stealthiest, work ispublicly exposing the most egregious polluters. It's enough to give a laid-offworker a sense of power and purpose. "I feel like a detective," saysJiang, laughing about her narrow escape at the paper mill. "But ordinarypeople like me have to get involved. Pollution is a problem that affects usall."

Two hundred miles northeast of Lanzhou, the Yellow Rivercarves a path through the desolate expanse of Ningxia, revealing a problem witheven more devastating long-term consequences than pollution: water scarcity.China starts at a disadvantage, supporting 20 percent of the world's populationwith just 7 percent of its fresh water. But it is far worse here in Ningxia, abone-dry region enduring its worst drought in recorded history. For millenniathe Yellow River was Ningxia's salvation; today the waterway is wasting away.Near the city of Yinchuan, the river's once mighty current is reduced to anarrow channel. Locals blame the river's depletion on the lack of rain. But thebiggest culprit is the extravagant misuse of water by rapidly expanding farms,factories, and cities.

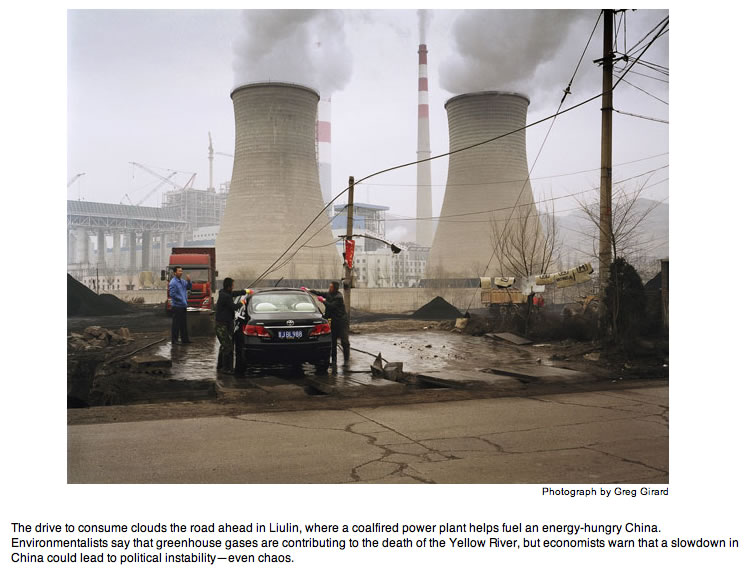

Perhaps every revolution, even a capitalist one, eats itschildren. But the pace at which China is squandering its most precious resourceis staggering. Judicious releases of reservoir water have averted theembarrassment of recent years, when the Yellow River ran completely dry. Butthe river's outflow remains just 10 percent of the level 40 years ago. Wherehas all the water gone? Agriculture siphons off more than 65 percent, half ofwhich is lost in leaky pipes and ditches. Heavy industry and burgeoning citiesswallow the rest. Water in China, free until 1985, is still so heavilysubsidized that conservation and efficiency are largely alien concepts. And thesiege of the Yellow River isn't about to stop: In 2007 the government approved52 billion dollars in coal mining and chemical industries to be installed alonga 500-mile stretch of the river north of Yinchuan.

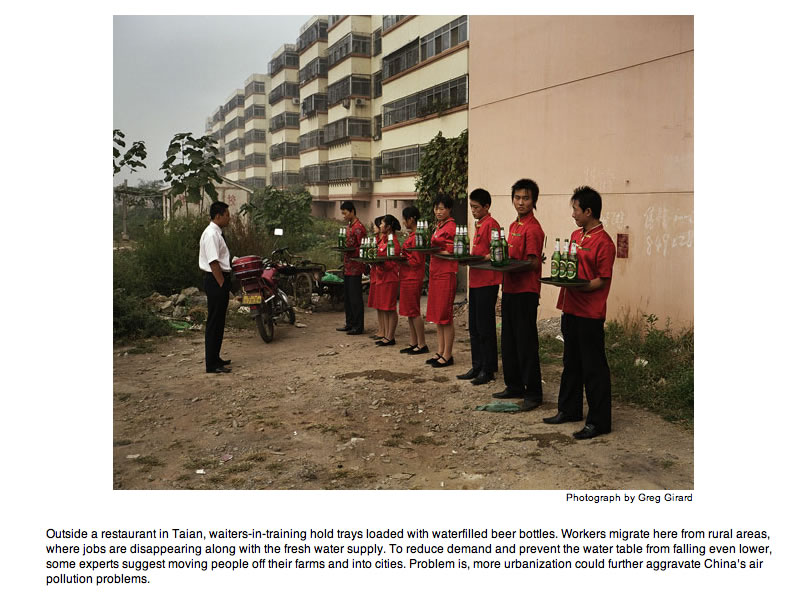

Such frenzied growth may soon fall victim to the very watercrisis it has helped create. Of the some 660 cities in China, more than 400lack sufficient water, with more than a hundred of these suffering severeshortages. (Beijing is chronically short of water too, but it will be sparedduring the Olympics, thanks to engineering feats that divert water from theYellow River.) In a society increasingly divided between urban and rural, richand poor, it is China's vast countryside—and its 738 million peasants—thatbears the brunt of the water shortage.

The lack of water is already hindering China's grainproduction, fueling concerns about future shocks to global grain markets, whereeven modest price hikes can have a disastrous effect on the poor. WangShucheng, China's former minister of water resources, put the situationdramatically: "To fight for every drop of water or die, that is thechallenge facing China."

For Sun Baocheng, a sunbaked 37-year-old farmer from thecentral Ningxia village of Yanghe, this challenge is not merely rhetoricalexcess. Two years ago, after their wells and rain buckets went dry fromdrought, all 36 families in Yanghe abandoned their village to the encroachingdesert. They came to a valley called Hongsipu, where more than 400,000environmental refugees have settled for one reason: It has water, delivered bya Kuwaiti-funded aqueduct that snakes across the scrub desert from the YellowRiver, 20 miles to the north. The Yanghe villagers have settled in a row ofsingle-room brick houses near the concrete aqueduct, tending plots of landgiven by the Chinese government (along with about $25 a person) as part of aprogram to alleviate poverty and desertification.

Even though Sun is barely able to coax a few stalks of cornout of the sandy soil, he is inspired by the flourishing crops—and growingwealth—of more established refugees. "If we hadn't left our old villageand come here," he says, "we wouldn't have survived." The MotherRiver, once again, is giving life. But with all the pressures on its dwindlingwater, one wonders: What will creating another oasis in the desert do to theriver's own chances of survival?

Mao Zedong's mantra—"Sacrifice one family, save 10,000families"—is still seared into Wang Yangxi's memory. Like the Chineseemperors before him, Chairman Mao was obsessed with taming the Yellow River, thelife-giving force whose changes of course also unleashed devastating floods,earning it the enduring sobriquet "China's Sorrow." When, in 1957,construction began on the massive dam at Sanmenxia, on the river's middlesection, 400,000 people—including Wang—lost their homes. Mao's slogan convincedthem it was a noble sacrifice. "We were proud to help the nationalcause," says Wang, now 83. "We've had nothing but misery eversince."

The idea of conquest has driven China's approach to natureever since Yu the Great, first ruler of the Xia dynasty, allegedly declaredsome 4,000 years ago: "Whoever controls the Yellow River controlsChina." Mao took this, like much else, to extremes. His biggest monumentto man's power over nature—the 350-foot-tall Sanmenxia Dam—is a case study inthe danger of unintended consequences. The dam has tamed the lower third of theYellow River by turning it into what one commentator has called "thecountry's biggest irrigation ditch." But the impact upriver has been disastrous,due to a stunning lack of foresight. Engineers failed to account for thecolossal amount of yellowish silt (more than three times the sediment dischargeof the Mississippi) that gives the river its name. By mismanaging the silt,Sanmenxia has caused as many floods as it has prevented, ruined as many livesas it has saved, and compelled the construction of another huge dam simply tocorrect its mistakes. One of Sanmenxia's original engineers even recommendsblowing up the whole thing.

Wang would be the first to volunteer for such a mission.Husking cotton on his doorstep in Taolingzhai village, about 30 miles west ofSanmenxia, the bristle-haired former schoolteacher recalls a life whose everytragic twist has been shaped by the dam. After Wang and his family were evictedfrom this fertile land during the dam's construction, they were banished to adesert region 500 miles away. Nearly a third of the refugees died of starvationduring Mao's Great Leap Forward, he says. Eventually, half of the survivorsstraggled home. Wang now farms land near the junction of the Wei and YellowRivers. But even here, he is not safe. When heavy rains fall, the Sanmenxiareservoir backs up, pushing polluted water over the banks. Three floods in fiveyears have destroyed his cotton crops and poisoned the village's drinkingsupply. "All of our young people have left," says Wang. "There'sno future here."

Unlike Mao's little red book, the Sanmenxia Dam is hardly arelic of the past. China now boasts nearly half of the world's 50,000 largedams—three times more than the United States—and construction continues. Acascade of 20 major dams already interrupt the Yellow River, and another 18 arescheduled to be built by 2030. Grassroots resistance to dams has emerged, mostfamously over the forced resettlement of more than a million people by theYangtze River's Three Gorges Dam, but to little effect. Ma Jun, a prominentenvironmentalist, says dams on the Yellow River are especially harmful, sincethey exacerbate the twin threats of pollution and scarcity. The reduced waterflow destroys the river's ability to flush out heavy pollutants, even asstanding reservoirs allow a badly overused river to be drained even further. "Why cannot human beings give up their ruthless ambition of harnessing andcontrolling nature," Ma asks, "and choose instead to live in harmonywith it?"

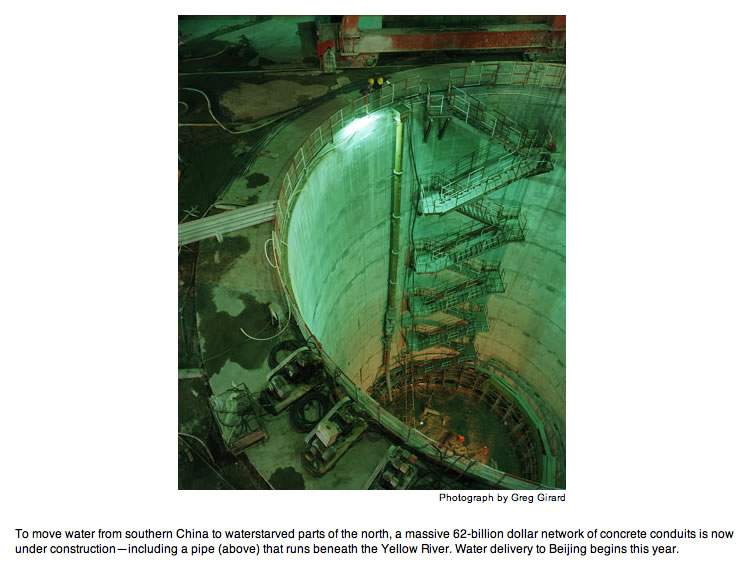

The simple answer: Beijing is still addicted to growth. Theeconomic boom has lifted hundreds of millions of Chinese out of poverty, andthe Communist Party's legitimacy, perhaps even its survival, depends oncontinued expansion. China's leaders pay lip service to conservation andefficiency as a solution to the north's chronic water shortage. But rather thanraise the price of water to true market levels—a move that would surelyalienate both the masses and big industry—they have opted instead for anotherpharaonic feat of engineering: the South-to-North Water Transfer Project. The62-billion-dollar canal system, which is designed to relieve pressure on theYellow River, will siphon some 12 trillion gallons of water a year from theYangtze Basin and send it 700 miles north, passing beneath the Yellow in twoplaces. It's no surprise, given the Olympian scale of the project, that it—likeSanmenxia—originated as one of Mao's pipe dreams.

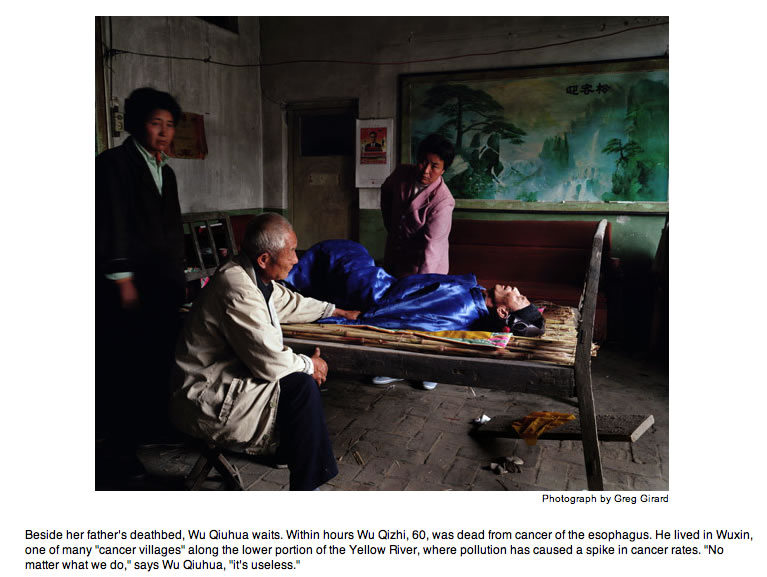

Even as other parts of China careened through droughts andfloods in past decades, the village of Xiaojiadian enjoyed a steady supply offresh water by virtue of its location on a tributary of the Yellow River, lessthan 200 miles from where it spills into the sea. But the waters, once a sourceof life, have turned deadly. Nobody here likes to talk about the plague thathas struck the village, but the scar running down the chest of a gaunt farmernamed Xiao Sizhu has its own eloquence. It shows precisely where doctors triedto remove the cancerous tumor gnawing at his esophagus. In between bites ofsodden bread—one of the only foods he can digest—Xiao, 55, whispers about theold days, when his family felt lucky to live in this well-watered corner of theriver basin, in eastern Shandong Province. Over the past two decades, however,a parade of tanneries, paper mills, and factories arrived upstream, dumpingwaste directly into the river. Xiao used to swim and fish in the eddy next tothe village well. Now, he says, "I never go close to the water because itsmells awful and has foam on top."

Another place he avoids is the grove of poplar trees outsidethe village, with its burial mounds stretching to the river's edge. In the pastfive years more than 70 people in this hamlet of 1,300 have died of stomach oresophageal cancer. More than a thousand others in 16 neighboring villages havealso succumbed. Yu Baofa, a leading Shandong oncologist who has studied thevillages of Dongping County, calls it "the cancer capital of theworld." He says the incidence of esophageal cancer in the area is 25 timeshigher than the national average.

The more than four billion tons of wastewater dumpedannually into the Yellow River, accounting for a full 10 percent of the river'svolume, has pushed into extinction a third of the river's native fish speciesand made long stretches unfit even for irrigation. Now comes the human toll. Ina 2007 report China's Ministry of Health blamed air and water pollution for analarming rise in cancer rates across China since 2005—19 percent in urban areasand 23 percent in the countryside. Nearly two-thirds of China's ruralpopulation, more than 500 million people, use water contaminated by human orindustrial waste. It's little wonder that gastrointestinal cancer is now thenumber one killer in the countryside.

The ubiquity of pollution-related disease is cold comfort tothe villagers in Xiaojiadian, who live in fear and shame. The fear isunderstandable: 16 more cases of cancer were diagnosed in the village lastyear. The shame, however, has deeper roots. Even though officials toldvillagers the epidemic likely stems from the drinking well by the poisonedriver, many locals believe cancer comes from an imbalance of chi, or life force,which is said to occur more frequently in those with quick tempers or badcharacters.

Like most victims, Xiao suffered in silence in his house fornearly a year, hiding his symptoms even from the local doctor. Medical billshave since wiped out his savings, and the tumor has reduced his voice to awhisper. Even so, Xiao is one of the few willing to speak out. "If wedon't talk, nothing gets done," he rasps, spitting up phlegm into aplastic cup. The government recently built a new well 11 miles away and sent inteams of doctors. But Xiao says officials might not have paid attention toXiaojiadian had a villager not tipped off a reporter at a Chinese televisionstation two years before. Now Xiao only has one regret: that he didn't speakout earlier. "It might have saved me," he says.

A few months pass, and a fresh earthen mound appears in thegrove of poplar trees by the river. The grave has no tombstone, just somebamboo sticks and a few aluminum cookie wrappers rustling in the breeze. Xiaohas come to the place he long avoided, joining friends and neighbors who werestalked by the same waterborne assassin. Is it a cruel irony or just thenatural order that their final resting place overlooks the very river thatlikely killed them?

It is too late to save Xiao Sizhu, but there remains aflicker of hope that the Yellow River can be rescued. China's leaders, aware ofthe peril their country faces, now vow "to build an ecologicalcivilization," setting aside almost 200 billion dollars a year for the environment.But the future depends equally on ordinary citizens such as activists ZhaoZhong and his mother, the intrepid Jiang Lin. Remember that Lanzhou paper millJiang locked in with her GPS? Not long after the information went up on theInternet, the government shut down the mill, along with 30 other factoriesdumping poison into tributaries of the Yellow River.

"Maybe the impact of one single person is small,"says Zhao. "But when it is combined with others, the power can behuge."