On a scorching August day in southwestern Indiana, the giantGibson generating station is running flat out. Its five 180-foot-high boilersare gulping 25 tons of coal each minute, sending thousand-degree steam blastingthrough turbines that churn out more than 3,000 mega-watts of electric power,50 percent more than Hoover Dam. The plant's cooling system is struggling tokeep up, and in the control room warnings chirp as the exhaust temperaturerises.

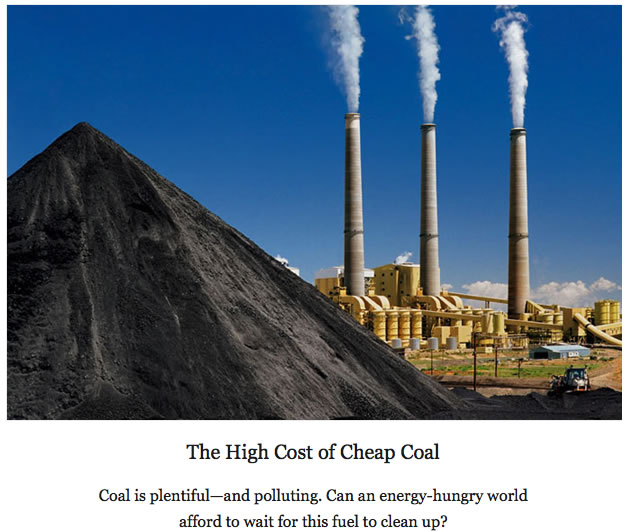

Next time you turn up the AC or pop in a DVD, spare athought for places like Gibson and for the grimy fuel it devours at the rate ofthree 100-car trainloads a day. Coal-burning power plants like this one supplythe United States with half its electricity. They also emit a stew of damagingsubstances, including sulfur dioxide—a major cause of acid rain—and mercury.And they gush as much climate-warming carbon dioxide as America's cars, trucks,buses, and planes combined.

Last summer's voracious electricity use was just a preview.Americans' taste for bigger houses, along with population growth in the Westand air-conditioning-dependent Southeast, will help push up the U.S. appetitefor power by a third over the next 20 years, according to the Department ofEnergy. And in the developing world, especially China, electricity needs willrise even faster as factories burgeon and hundreds of millions of people buytheir first refrigerators and TVs. Much of that demand is likely to be met withcoal.

For the past 15 years U.S. utilities needing to add powerhave mainly built plants that burn natural gas, a relatively clean fuel. But anear tripling of natural gas prices in the past seven years has idled manygas-fired plants and put a damper on new construction. Neither nuclear energynor alternative sources such as wind and solar seem likely to meet the demandfor electricity.

Mining enough coal to satisfy this growing appetite willtake a toll on lands and communities (see following story, page 104). Of allfossil fuels, coal puts out the most carbon dioxide per unit of energy, soburning it poses a further threat to global climate, already warming alarmingly.With much government prodding, coal-burning utilities have cut pollutants suchas sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides by installing equipment like thebuilding-size scrubbers and catalytic units crowded behind the Gibson plant.But the carbon dioxide that drives global warming simply goes up thestacks—nearly two billion tons of it each year from U.S. coal plants. Withinthe next two decades that amount could rise by a third.

A hundred miles up the Wabash River from the Gibson plant isa small power station that looks nothing like Gibson's mammoth boilers andsteam turbines. This one resembles an oil refinery, all tanks and silverytubes. Instead of burning coal, the Wabash River plant chemically transforms itin a process called coal gasification.

The syngas can even be processed to strip out the carbondioxide. The Wabash plant doesn't take this step, but future plants could. Coalgasification, Vick says, "is a technology that's set up for total CO2removal." The carbon dioxide could be pumped deep underground intodepleted oil fields, old coal seams, or fluid-filled rock, sealed away from theatmosphere. And as a bonus, taking carbon dioxide out of the syngas can leavepure hydrogen, which could fuel a new generation of nonpolluting cars as wellas generate electric power.

Yet that's no guarantee utilities will embrace thegasification technology. "The fact that it's proved in Indiana and Floridadoesn't mean executives are going to make a billion-dollar bet on it," says William Rosenberg of Harvard's Kennedy School of Government. The twogasification power plants in the U.S. are half the size of most commercialgenerating stations and have proved less reliable than traditional plants. Thetechnology also costs as much as 20 percent more. Most important, there'slittle incentive for a company to take on the extra risk and expense of cleanertechnology: For now U.S. utilities are free to emit as much carbon dioxide asthey like.

Cinergy CEO James Rogers, the man in charge of Gibson andeight other carbon-spewing plants, says he expects that to change. "I dobelieve we'll have regulation of carbon in this country," he says, and hewants his company to be ready. "The sooner we get to work, the better. Ibelieve it's very important that we develop the ability to do carbonsequestration." Rogers says he intends to build a commercial-scale gasificationpower plant, able to capture its carbon dioxide, and several other companieshave announced similar plans.

The energy bill passed last July by the U.S. Congress offershelp in the form of loan guarantees and tax credits for gasification projects. "This should jump-start things," says Rosenberg, who advocated thesemeasures in testimony to Congress. The experience of building and running thefirst few plants should lower costs and improve reliability. And sooner orlater, says Rogers, new environmental laws that put a price on carbon dioxideemissions will make clean technology look far more attractive. "If thecost of carbon is 30 bucks a ton, it's amazing the kinds of technologies thatwill evolve to allow you to produce more electricity with less emissions."

If he's right, we may one day be able to cool our houseswithout turning up the thermostat on the entire planet.