When world leaders meet in Copenhagen for the United Nations Climate Conference this week, some of the data they'll have at their fingertips will have come from a huge freezer on the Ohio State University campus.

Inside, at temperatures that hover around 30 below zero, are hundreds of ice cores removed from remote mountain glaciers, some of which are shrinking at an alarming rate.

Two of the caretakers are OSU climate researchers Lonnie Thompson and Ellen Mosley-Thompson, who directs the Byrd Polar Research Center.

Each cylinder of ice is a record of Earth's climate and can provide the evidence scientists rely on to help establish and illustrate global warming.

Byrd researchers are helping lead efforts to study the effects of climate change on the Arctic and Antarctic. They also have helped tie a steady rise in the world's oceans to vast, melting ice sheets in Greenland and the South Pole.

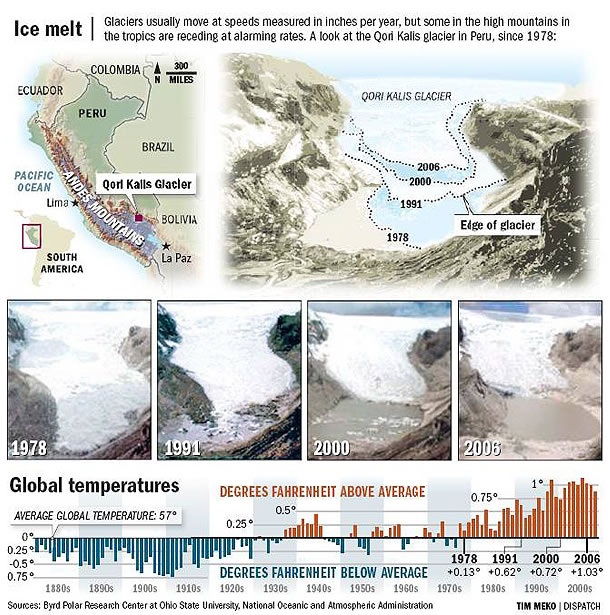

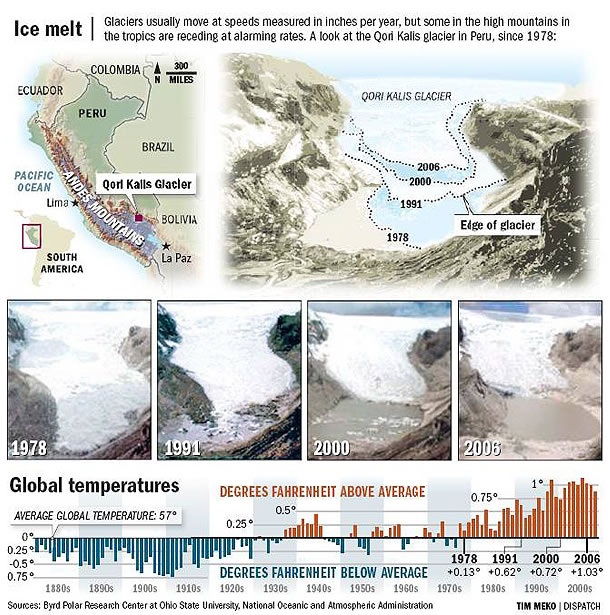

Shrinking glaciers

The Thompsons are among a group of scientists who discovered that glaciers in the tropics are shrinking and could disappear within decades.

They have seen the glaciers recede with their own eyes, but the cause is buried in the ice, where dust, pollen and gases reveal climate conditions over hundreds of thousands of years.

A 2006 paper that the couple published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences tied together decades of data taken from seven glaciers in South America and Asia.

They found that the retreat of tropical mountain glaciers is an event that until now hasn't been seen in at least 2,000 years.

Lonnie Thompson said the glaciers are disappearing as the result of increased average global temperatures brought about by the burning of fossil fuels and the clearing of Earth's forests.

"It's just phenomenal," he said. "If someone told me back when I started in the 1970s that glaciers would move like this, I would have said they were crazy."

Rising oceans

Water melting from these glaciers and from massive sheets of ice in Greenland and Antarctica also contributes to a rise in Earth's oceans, said C.K. Shum, a professor of geodetic science at the Byrd center.

Using more than a century of data recorded by tidal gauges, Shum said the average global sea level has risen between 1.7 millimeters and 1.8 millimeters a year throughout the 20th century.

And satellite data over the past 10 years show a more rapid rise of 3 millimeters to 3.5 millimeters per year.

Shum also is a lead author of "Ocean Climate and Sea Level," a chapter in the International Panel on Climate Change's 2007 report, which summarized the state of knowledge on global warming and predicted its consequences.

He found that sea levels could rise 24 inches by the end of the century, which would swamp coastal cities and many small island nations.

Such predictions are difficult, Shum said. Part of the problem is that tidal gauges record levels at about only 1 percent of Earth's oceans. Though satellites cover the whole earth, there are only about 10 years of data to work with.

"A lot of things are evolving," Shum said.

Polar weather

Researchers also are scrambling to learn more about the effect of warming on polar regions, where annual losses of arctic sea ice have been dramatic.

David Bromwich, a professor of polar meteorology at the Byrd center, will help lead a four-year, multi-university and governmental project that will combine data from NASA satellites and weather stations with research on changes in permafrost, sea ice and polar region rivers.

"We need to get a more comprehensive view of what's happening," Bromwich said.

The challenge and the risks are enormous.

If all of the ice in Antarctica melted, it would raise the ocean levels by more than 213 feet, Bromwich said.

"You only have to lose a little bit of that ice and it makes quite a lot of difference," he said.