By John G. Mitchell

Photograph by Melissa Farlow

Originally printed in the National Geographic Magazine - March, 2006

By John G. Mitchell

Photograph by Melissa Farlow

Originally printed in the National Geographic Magazine - March, 2006

Coal brought people to marfork hollow in the Appalachian Mountains of southern West Virginia. And it was coal, or rather a different way of mining it, that finally drove the people away. The last to leave was Judy Bonds.

A coal miner's daughter whose roots here go back nine generations, Bonds packed up her family and fled when she could no longer tolerate the blasting that rattled her windows, the coal soot that she suspected was clotting her grandson's lungs, and the blackwater spills that bellied-up fish in a nearby stream. Retreating to the town of Rock Creek, a few miles downstream, Bonds joined Coal River Mountain Watch, a citizens group determined to oppose surface-mining abuses.

In the years since Bonds moved, coal companies have turned to an even more aggressive mining process known as mountaintop removal. After clear-cutting a peak's forest, miners shatter its rock with high explosives. Then they scoop up the rubble in giant draglines and dump the overburden, as they call it, into a conveniently located hollow, or valley. The method was first tested in Kentucky and West Virginia in the late 1970s and has since spread to parts of Tennessee and Virginia.

"What the coal companies are doing to us and our mountains," said Bonds when she and I first met years ago, "is the best kept dirty little secret in America."

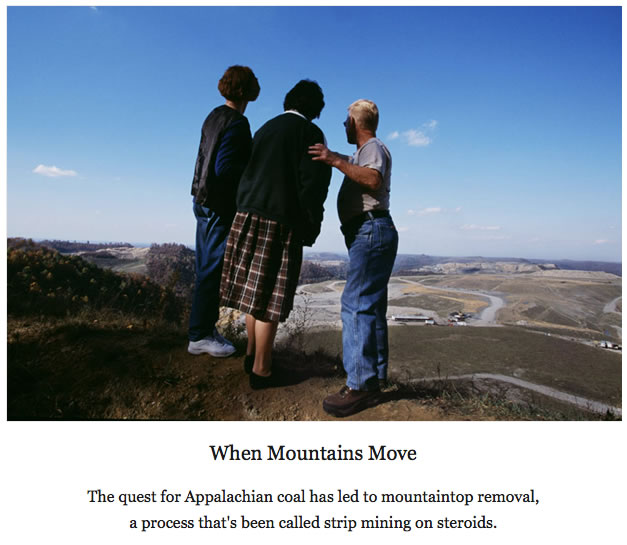

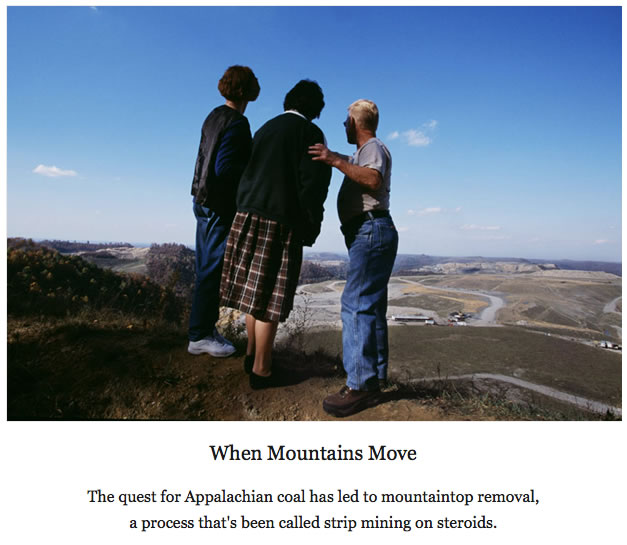

Now the secret is out. Coal companies have obliterated the summits of scores of mountains scattered throughout Appalachia, and more and more folks like Judy Bonds are decrying the environmental and social fallout of what some refer to as strip mining on steroids.

Not only is mountain topping less labor intensive than underground mining, it is also more efficient and profitable than the older form of surface mining, in which the operator stripped away the horizontal contours of a mountainside as one might peel an apple. So fast has the practice spread that there's no accurate accounting of the area affected, but surface mining in general has impacted more than 400,000 acres (1,600 hectares) in this four-state Appalachian region including more than 1,200 miles (2,000 kilometers) of streambeds. If the practice continues until 2012, it will have squashed a piece of the American earth larger than the state of Rhode Island.

In the years since high-tech earthmoving machinery made mountain topping increasingly attractive to the energy industry, more and more of West Virginia's total production of coal—some 154 million tons (140 million metric tons) in 2004—has come from its decapitated highlands. Relative to Western coal (Wyoming is the nation's top coal producer), second ranked West Virginia's low-sulfur bituminous burns with a cleaner, hotter efficiency in the electric power plants of America. And taxes from bituminous coal help fuel a large part of the state's economy.

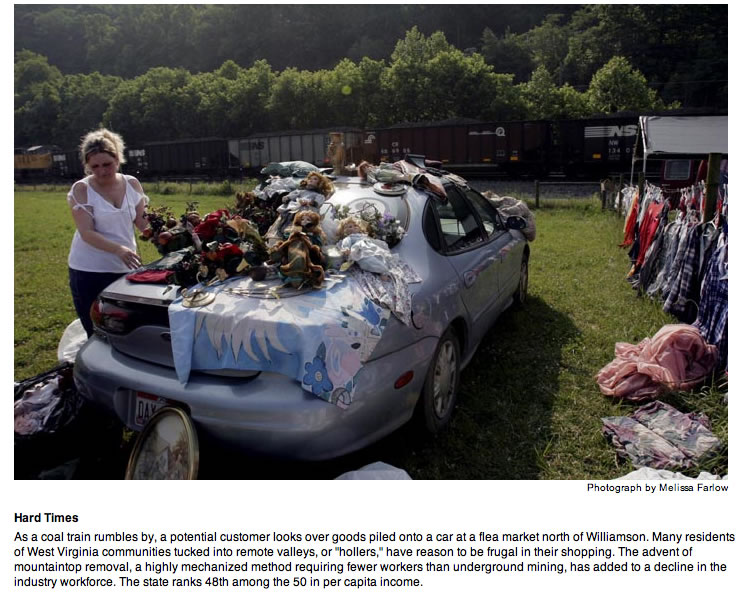

But some West Virginians have been paying a hurtful price for their state's good fortune—and the coal industry's cost-cutting efficiency. In 1948 some 125,000 men worked in the mines of West Virginia. By 2005 there were fewer than 19,000, and most of these were employed in underground mines. Nowadays, it just doesn't take many hands to wrestle coal off the top of a mountain.

Consider, for example, the Big Coal River community of Sylvester, where fewer than 20 of its 195 longtime residents are employed in mining or related services. And consider Sylvester resident Pauline Canterberry. She lives in a small house just a quarter mile down State Route 3 from a coal-washing plant operated by the Elk Run Coal Company, a subsidiary of Massey Energy, West Virginia's premier producer. Canterberry has been waging a decade-long battle with Massey and state and federal regulators over the volume of coal dust wafting from the Elk Run facility and sifting under the sills of Sylvester's homes. She has personal reasons for being concerned about the quality of the air. Her father, Ernest Spangler, died in 1957 from silicosis. His job had been putting out mine fires with buckets of pulverized rock dust. Then in 1991 her husband, John D. Canterberry, died of black lung disease after years of working in underground mines.

"When I was young, Sylvester was the place to be," Canterberry said. "Everyone wanted a home here because the town was so clean. It wasn't a company town. But then Massey came into the valley, and it's been downhill ever since—in more ways than one. Now they'll take 300 feet (90 meters) off the top of a mountain just to get at a few feet of coal."

After a long succession of petitions and hearings, 150 Sylvester residents prevailed in their case against Elk Run, forcing the company to pay the litigants economic damages of nearly half a million dollars and requiring it to maintain a dust-trapping dome over its processing plant and to limit the number of coal trucks passing through town to an average of 20 a day. Despite these concessions, Canterberry and some of her activist neighbors are worried about Massey's plans to expand its Elk Run operations. (Massey representatives did not return repeated phone calls requesting information on its record at Sylvester.)

Several years ago the director of the state's Division of Mining and Reclamation issued a memorandum showing that for the years 2000 and 2001 Massey incurred 500 violations, more than twice the number accumulated by the state's next three largest producers combined. Sixty-two of those violations, most involving excessive coal dust emissions, were attributed to the Elk Run Coal Company at Sylvester.

I grew up beholden to West Virginia bituminous coal. My parents' house in Cincinnati was heated by it until they switched to oil in 1945. The coal came down the Ohio River by barge, and every wintry month or so a dump truck would deliver a big pile beside our garage. I remember helping my father cart it to the furnace inside, and the grating screech of his shovel on the cellar floor. And I remember the trail of black soot and the coal dust on my shoes. I was grateful for the warmth the coal gave us, but I hated it too because it was dirty. This was before public health and clean-air regulations obliged the mining industry to wash coal and, in Appalachia at least, dispose of the dust, dirt, and wastewater in impoundments, often perched precariously on the sides of the mountains.

There are some 500 of these impoundments in Appalachia today, more than half in Kentucky and West Virginia. Variously referred to as slurry ponds, sludge lagoons, or waste basins, they impound hundreds of billions of gallons of toxic black water and sticky black goo, by-products of cleaning coal, mostly from underground mines but also from surface mines. Mountain folk residing downhill from these ponds worry about what a flood of loose sludge might do—and has already done in a number of tragic cases.

In Logan County in the winter of 1972, following two straight days of torrential rain, a coal-waste structure built by a subsidiary of the Pittston Coal Company collapsed and spilled 130 million gallons (492 million liters) into Buffalo Creek. The flood scooped up tons of debris and scores of homes as it swept downstream. Survivors recalled seeing houses bob by, atilt in the swift current, the doomed families huddled at their windows. The final count was 125 dead, 1,000 injured, 4,000 made homeless. The Pittston Company called the disaster an "act of God."

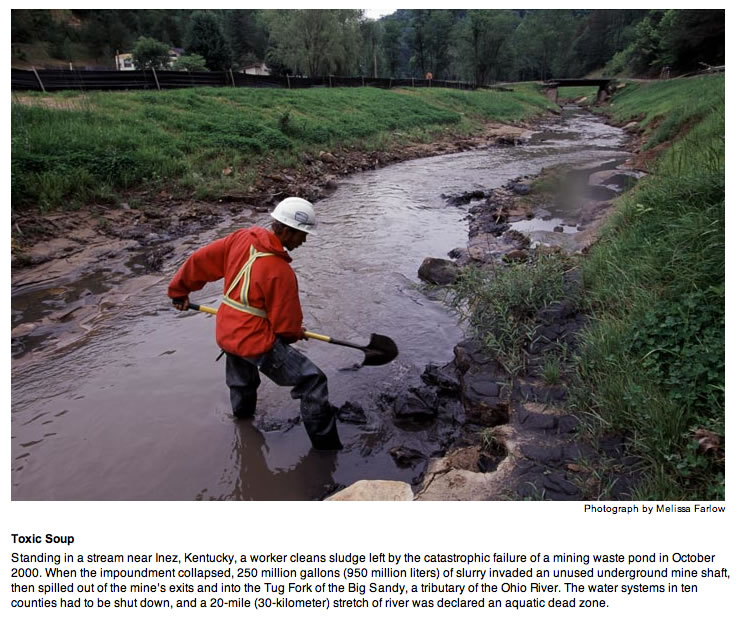

In neighboring Kentucky on an October morning in 2000, the bottom of a waste pond near the town of Inez collapsed, pouring 250 million gallons (946 million liters) of slurry—25 times the amount of oil spilled in the Exxon Valdez disaster—into an inactive underground mine shaft. From there, the slurry surged to the mine's two exits and flooded two creeks hell-bent for the Tug Fork of the Big Sandy and the Ohio River beyond. Miraculously, there was no loss of human life, though 20 miles (32 kilometers) of stream valley would be declared an aquatic dead zone, water systems in ten counties would have to be shut down, and the black slick would eventually reach out toward the riverfront in Cincinnati. Lawyers for the Martin County Coal Company, a Massey subsidiary and owner of the impoundment, blamed the accident on excessive rainfall, which was simply another way of saying what had been said at Buffalo Creek. It was God's fault.

Fear of impoundment failures haunts the collective memory of West Virginians. "I'm convinced something awful's going to happen again," Freda Williams was saying the day I called on her at her tidy brick house beside a tributary of the Big Coal River, just south of Whitesville. One of the largest waste basins in the state, the Brushy Fork slurry lagoon, owned by Massey Energy, impounds some eight billion gallons of blackwater sludge about three miles upstream from Williams's home.

"What's going to happen to all that water if the dam breaks or the basin collapses into an abandoned underground mine?" By some accounts, should the Brushy Fork impoundment ever fail, a wave of sludge 25 feet (7 meters) high could roll over Whitesville in no time flat.

Two other Massey waste impoundments pucker the slopes of the Big Coal Valley. The one at Sundial looms directly above the Marsh Fork Elementary School, with an enrollment of 240 children, from kindergarten through fifth grade. Though Stephanie Timmermeyer, chief of the state's Department of Environmental Protection, has claimed that the Massey facility poses no threat to the schoolchildren, the agency's own rating system lists the dam as a Class C facility, meaning its failure could reasonably be expected to cause loss of human life.

Besides the raw scars of the mines themselves, the most startling features of coal country are not necessarily those blackwater basins but the mountain-topped valley fills that have buried hollows and headwater streams under millions of tons of broken rock. Critics fear some fills could eventually come tumbling down in landslides of unpredictable proportions. As one Kentucky attorney likes to put it: "A valley fill is a time bomb waiting to happen."

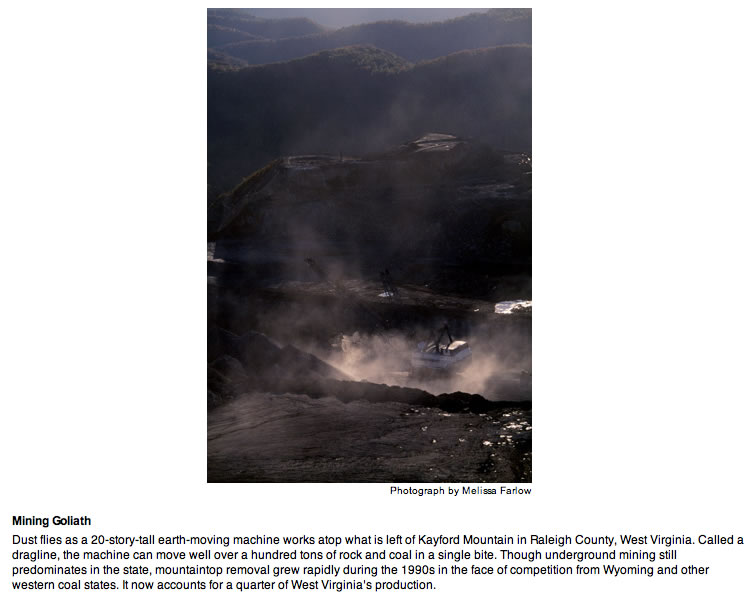

One of West Virginia's biggest time bombs reaches more than two miles down what used to be, when it was flowing free, the Connelly Branch of Mud River in Lincoln County. The fill represents part of a mountaintop the Arch Coal Company unhinged to create the 12,000-acre (4,800-hectare) Hobet 21 mine, one of the largest surface mines in West Virginia. But Hobet 21, now owned by Magnum Coal, has another distinction: For several years it's been home to "Big John," an earthmoving machine with a 20-story dragline and a bucket scoop that swallows over 100 tons of soil and rock in a single bite.

Up the Mud River a short way, a tributary known as Laurel Branch flows sweet and clear beside a weathered white-frame farmhouse. The front porch overlooks a garden of corn and potatoes. From the porch in the spring you can hear the vernal murmur of the creek, though not when the farmhouse is crowded, as it was at the time of my visit, with kin of the Caudill-Miller clan gathered at a place that has been in the family for a hundred years. Leon and Lucille Miller preside as host and hostess for these occasions. She is one of the surviving heirs of John and Lydia Caudill, who inherited 75 acres (30 hectares) abutting the Mud and built this farmhouse in 1920. Lucille was raised here, along with nine siblings. But now, for all the copious country food and Caudill hospitality, an explicable uneasiness lingered at the edge of the festivities. Moving to expand its Hobet 21 operation, Arch Coal had informed the Millers that it was looking to do with Laurel Branch what it had done to the Connelly. And Arch wanted the Caudill homeplace out of the way.

"They want it all," Leon Miller told me, "the house and everything. And we're saying, 'No.'"

Since that particular May reunion a few years ago, I have been following the ups and downs of the Millers' struggle to stop Arch Coal from burying Laurel Branch and the ancestral home under the shadow of Hobet 21. Arch did succeed in buying out some of the Caudill heirs, thereby acquiring a two-thirds interest in the 75 acres (30 hectares). But when Lucille Miller and six of the heirs continued to say "no," Arch's Ark Land Company filed a lawsuit in Lincoln County Circuit Court arguing that the holdouts should be forced to sell their interests because coal mining was "the highest and best use of the property" and because the cost of protecting the nearby MillerCaudill land from mining waste would be prohibitive for Arch. Besides, the company's attorneys said, the heirs did not live at the farm but used it only on weekends and other occasions. The circuit court ruled in the company's favor and ordered the property sold at auction. Arch got it. The Millers appealed to the state supreme court and won a reversal of the lower court's ruling. The farmhouse still stands, and the Laurel still murmurs, at least for now.

While Millers and Caudills rallied round their embattled homeplace, a larger but not unrelated issue was unfolding in federal courts and among the agencies responsible for regulating coal mining under the Clean Water Act and the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 (SMCRA). Under "Smackra," as the act is known, environmentalists contend that the U.S. Office of Surface Mining should enforce a buffer-zone rule prohibiting, in all but the most exceptional cases, any mining activity within one hundred feet of a stream. Under the Clean Water Act, the Army Corps of Engineers was supposed to regulate the actual filling of the streambed itself.

Perceiving a lack of enforcement on both counts, opponents of mountaintop mining in West Virginia have been in and out of court for the past five years, occasionally winning a legal round only to have it set aside on appeal by attorneys for various agencies and the coal industry.

In or out of the courtroom, the argument often boils down to differing opinions as to what constitutes a regulated stream in Appalachia, how vital its uppermost reaches might be to the ecological health of the downstream watershed, and finally the degree to which valley fill might contribute to flooding in a peak storm event.

The defenders of valley fills argue that most of these structures affect intermittent streams only and therefore do not fall within the reach of the Army Engineers and the Clean Water Act. William Raney, president of the West Virginia Coal Association, believes many fill areas are simply "dry hollows" for most of the year, implying that they serve little ecological function.

But that's not the way Ben Stout, a biology professor at Wheeling Jesuit University, sees it. According to Stout, aquatic insects in seep springs at the top of a watershed feed larger life-forms by shredding leaf litter and sending the nutrient-rich particles downstream. "These insects provide the link between a forest and a river," Stout says. "Bury their habitat and you lose the link."

The issue of flooding also evokes conflicting views. Raney sees no connection between mountaintop mining and floods. "Science doesn't bear that out," he told me during an interview in his Charleston office. "What causes flooding is too much water falling in too short a time."

Yet a study by federal regulators, obtained by the Charleston Gazette through the Freedom of Information Act, predicted that one valley fill at the Hobet 21 mine could increase peak runoff flow by as much as 42 percent. Vivian Stockman, a project coordinator with the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition in Huntington, contends that 12 West Virginians have died since 2001 because of floods related to mountaintop mining. "Old-timers will tell you property that has been in their families for generations never flooded severely until mining began upstream," Stockman says. "It's common sense. Denuded landscapes don't hold water the way forests do."

It was not the intent of Smackra, of course, to allow coal companies to walk away from their surface mines and leave them denuded. Stripped mountainsides, the law declared, must be restored to their "approximate original contour" and stabilized with grasses and shrubs, and, if possible, trees. But putting the entire top of a topped-off mountain back together again was an altogether different—and more expensive—matter. So mountaintop mines were given a blanket exemption from this requirement with the understanding that, in lieu of contoured restoration, the resulting plateau would be put to some beneficial public use. Coal boosters claimed the sites would create West Virginia's own Field of Dreams, seeding housing, schools, recreational facilities, and jobs galore. In most cases it didn't work out that way. The most common "use" turned out to be pastureland (in a region ill-suited for livestock production) or what the industry and its regulators like to identify as fish and wildlife habitat.

"The coal companies have stripped off hundreds of thousands of acres," says Joe Lovett, an attorney for the Appalachian Center for the Economy and the Environment, "but they're putting less than one percent of it into productive use."

Yet the industry should get some credit for what it's managed to accomplish in post-mining land use over the years. It's provided a number of West Virginia counties with the flat, buildable space to accommodate two high schools, two "premier" golf courses, a regional jail, a county airport, a 985-acre complex for the Federal Bureau of Investigation near Clarksburg, an aquaculture facility, and a hardwood-flooring plant in Mingo County that now employs 250 workers.

"Economically, we were dying on the vine," said Mike Whitt, executive director of the Mingo County Redevelopment Authority, as we toured the 40-million-dollar flooring plant, financed by grants from federal, state, and local governments and by private investors. "So we got OPM —other people's money—to get the job done. Without the infrastructure to create jobs, you're out of the game."

One emerging idea to help keep this under-employed region in the game is commercial forestry—restoring the land not as pasture or golf course or school but as a reincarnation of what used to be here in the rich diversity of the Appalachian forest. Arch Coal, with test plantings already established east of Whitesville, reports it's eager to pursue this option. "Our intent," says Arch's Larry Emerson, "is not just to approximate what was there before mining but, for the long range, establish a commercial forest."

Some foresters are not convinced that Arch is willing to go far enough in its romance with reforestation. James Burger, a professor of forestry at Virginia Tech University and a zealous proponent of turning topless mountains into productive forests, has found in his studies that weathered brown sandstone soils—making up a mountaintop's uppermost layer and therefore the first to be dumped and lost in a valley fill—would be better set aside and used, without compaction, as top dressing for any reforestation. But Arch's forestry consultant argues this would raise substantially the per-acre cost of reclamation.

A few environmentalists, such as Joe Lovett of the Appalachian Center, hail Burger's crusade for reforestation as the next best thing to stopping mountaintop mining altogether. Others view it as a cop-out exercise in wishful thinking. "I understand what makes up that forest, and it's not just trees," says Judy Bonds of Coal River Mountain Watch. "I'm talking about the herbs and the plants that evolved here in this forest over thousands of years. Re-create that forest? You couldn't do it in 1,500 years."

Standing in the doorway of the Mountain Watch office on the main street of Whitesville, I listened to Judy Bonds reminisce about the way it was 50 years ago when she was a child. "I used to swim in the Coal River then," she said, "but now it's so full of silt that the water barely comes up to your knees. It breaks my heart. I look at my grandson, and I see that he's the last generation that will hunt and fish in these mountains and dig for ginseng, and actually know mayapple when he sees it. These mountains are in our soul. And you know what? That's what they're stealing from us. They're stealing our soul."