Vanishing Amphibians

Originally published in the National Geographic Magazine, April of 2009 issue.

Vanishing Amphibians

Originally published in the National Geographic Magazine, April of 2009 issue.

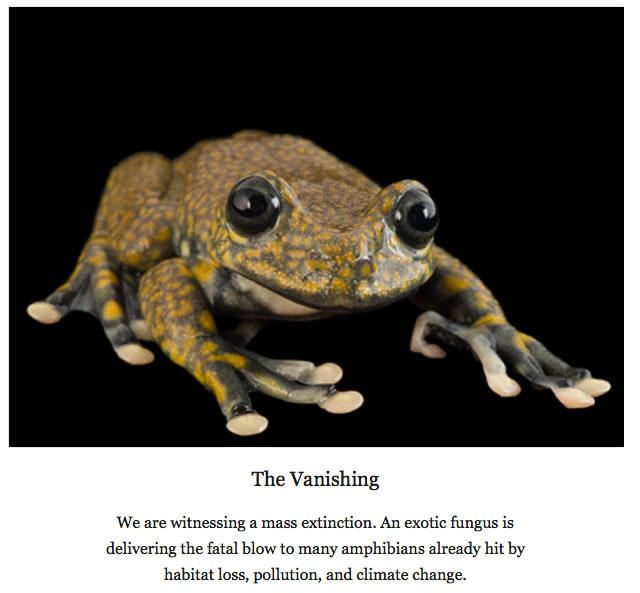

He grips his mate, front legs clasped tight around her torso.Splayed beneath him like an open hand, she lies with her egg-heavybelly soaking in the shallow stream. They are harlequin frogs of a rareAtelopus species, still unnamed and known only in a thin wedgeof the Andean foothills and adjacent Amazonian lowlands. The femaleappears freshly painted - a black motif on yellow, her underside shockingred. She is also dead.

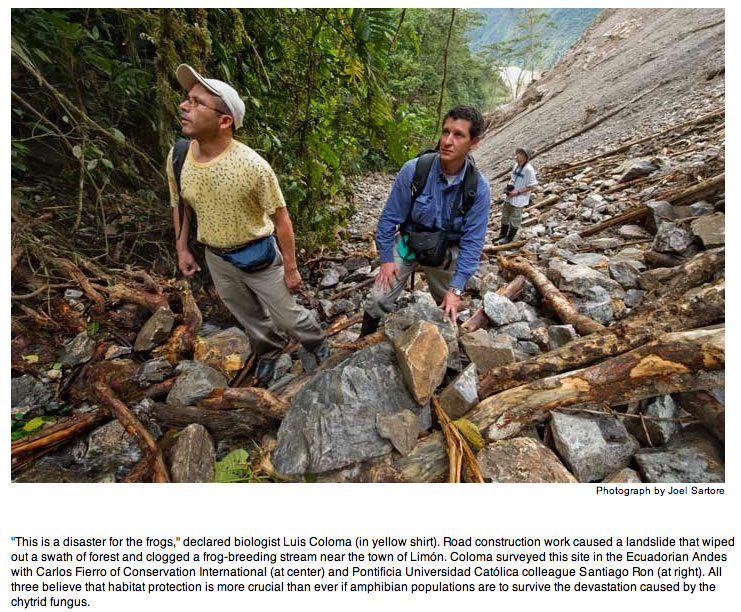

Above this tableau, at the lip of the ravine, a bulldozer idles.Road construction here, near the town of Limon in southeastern Ecuador,has sent an avalanche of rocks, broken branches, and dirt down thehillside, choking part of the forest-lined stream. Luis Coloma stepsgingerly over the loose rocks, inspecting the damage to the waterway.The 47-year-old herpetologist is bespectacled and compact in a yellowshirt dotted with tiny embroidered frogs. He hasn't bothered to roll uphis khaki pants, which are soaked to the knees. Poking a stick into thedebris, he says, "They have destroyed the house of the frog."

Frogs and toads, salamanders and newts, wormlike (and little-known)caecilians - these are the class Amphibia: cold-blooded, creeping,hopping, burrowing creatures of fairy tale, biblical plague, proverb,and witchcraft. Medieval Europe saw frogs as the devil; for ancientEgyptians they symbolized life and fertility; and for children throughthe ages they have been a slippery introduction to the natural world.To scientists they represent an order that has weathered over 300million years to evolve into more than 6,000 singular species, asbeautiful, diverse - and imperiled - as anything that walks, or hops, theEarth.

Amphibians are among the groups hardest hit by today's many strikesagainst wildlife. As many as half of all species are under threat.Hundreds are sliding toward extinction, and dozens are already lost.The declines are rapid and widespread, and their causes complex—even atthe ravine near Limon the bulldozer is just one hazard of many. Butthere are glimmers of hope. Rescue efforts now under way will sheltersome animals until the storm of extinction passes. And, at least in thelab, scientists have treated frogs for a fungal disease that isdevastating populations around the world.

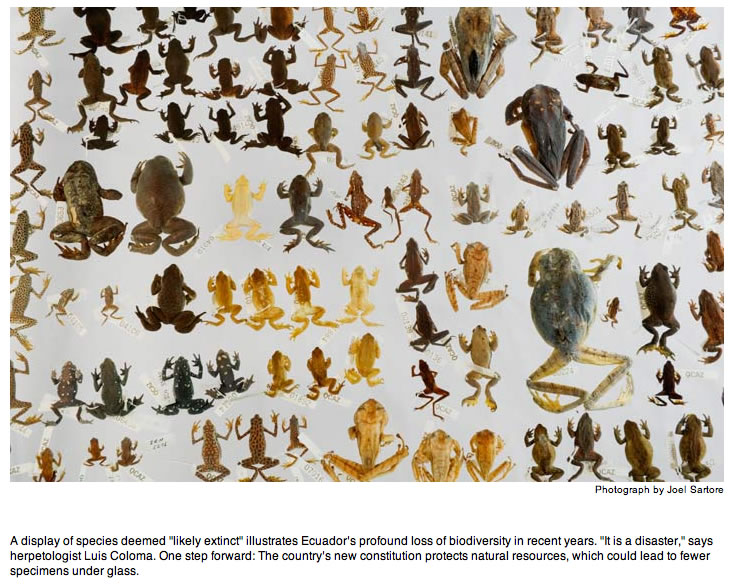

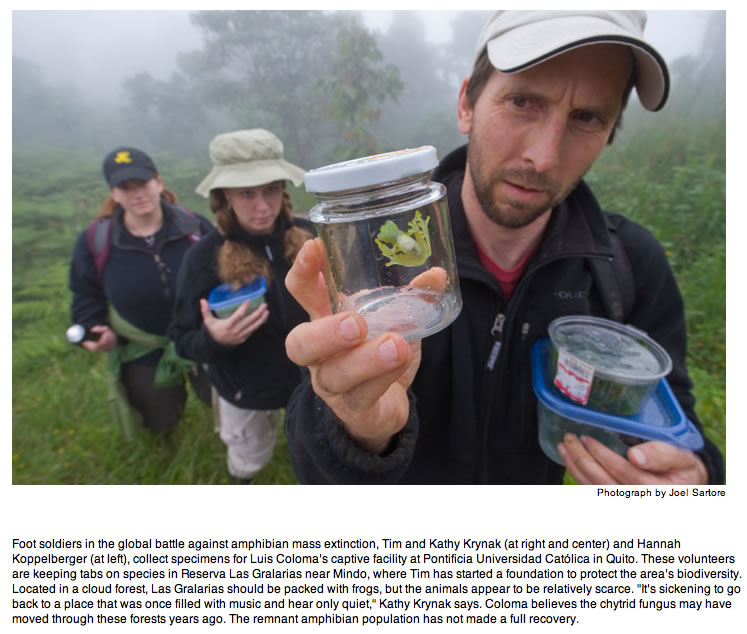

In Quito, Coloma and his colleague Santiago Ron have established acaptive-breeding facility for amphibians at the zoological museum atPontificia Universidad Catolica del Ecuador.They admit it's a drop inthe pond, offering safe harbor to a select few in hopes of stemmingnational losses. The facility houses just 16 species, although Ecuadoris home to more than 470. And that's just what's on the books. Despiteheavy deforestation across this country, every year new species arediscovered. Coloma's lab has about 60 recently discovered species stillawaiting scientific names - enough to keep ten taxonomists hard at workfor a decade.

Coloma and Ron, who have also initiated land purchases for habitatprotection, hope to add room at the captive facility for more than ahundred species. But the pool of wild animals is shrinking fast. Wherefield scientists once had to watch their step to avoid crushing frogsmoving in mass migrations, now counting a dozen feels like a victory."We're becoming paleontologists, describing things that are alreadyextinct," Ron says. At the Quito lab the evidence is stacked high.Coloma holds up one jar from a cabinetful. Two pale specimens bob inalcohol. "This species," he says, his face distorted through the glass,"went extinct in my hands."

It's no wonder some view our time on Earth as a mass extinction.Biodiversity losses today have reached levels not seen since the end ofthe Cretaceous period 65 million years ago. Yet amphibians were able tohold on through past extinction spasms, surviving even when 95 percentof other animals died out, and later when the dinosaurs disappeared. Ifnot then, why now?

"Today's amphibians have taken not just a one-two punch, but aone-two-three-four punch. It's death by a thousand cuts," saysUniversity of California, Berkeley, biologist David Wake. Habitatdestruction, the introduction of exotic species, commercialexploitation, and water pollution are working in concert to decimatethe world's amphibians. The role of climate change is still underdebate, but in parts of the Andes, scientists have recorded a sharpincrease in temperatures over the past 25 years along with unusualbouts of dryness.

But a form of fungal infection, chytridiomycosis (chytrid forshort), often administers the coup de grace. It did for the mating pairin the Limon stream. Both animals tested positive for chytrid fungus,and the male died soon after the female.

Chytrid was wiping out amphibians in Costa Rica back in the 1980s,although no one knew it at the time. When frogs started dying in bignumbers in Australia and Central America in the mid-1990s, scientistsdiscovered the fungus was to blame. It attacks keratin, a keystructural protein in an animal's skin and mouthparts, perhapshampering oxygen exchange and control of water and salts in the body.African clawed frogs, exported widely for pregnancy tests beginning inthe 1930s, may have been the initial carriers of the fungus. "It'samazing we haven't seen even more population crashes, the way weshuffle things all over the world, complete with pathogens," notes RossAlford of Queensland's James Cook University.

Chytrid is now reported on all continents where frogs live - in 43countries and 36 U.S. states. It survives at elevations from sea levelto 20,000 feet and kills animals that are aquatic, land-loving, andthose that jump the line. Locally it may be spread by anything from afrog's legs to a bird's feathers to a hiker's muddy boots, and it hasafflicted at least 200 species. Gone from the wild are the Costa Ricangolden toad, the Panamanian golden frog, the Wyoming toad, and theAustralian gastric-brooding frog, to name a few. Some scientists playdown the importance of any single factor in overall declines. But in a2007 paper, Australian researcher Lee Berger and colleagues, who firstlaid blame on the fungus, put it this way: "The impact ofchytridiomycosis on frogs is the most spectacular loss of vertebratebiodiversity due to disease in recorded history."

It's been a time of desperate measures. For example, after SouthernIllinois University researcher Karen Lips and colleagues reportedfungus-related declines in Costa Rica and Panama in the late 1990s,they began mapping chytrid's path and predicting its victims. By 2000,teams were grabbing up animals from the most vulnerable species tostash them away - at zoos, at hotels, anywhere temporary space could becarved out for stacks of aquariums. Sick frogs were treated andquarantined. Many were exported (with much political wrangling) to U.S.zoos, while a Panamanian facility was built to house nearly a thousandanimals. So began the Amphibian Ark, a growing international ventureaimed at keeping at least 500 species in captivity for reintroductionwhen - if - the crisis is resolved. But the task is immense and expensive,and there's no guarantee how many healthy wild places will be left foramphibians to recolonize.

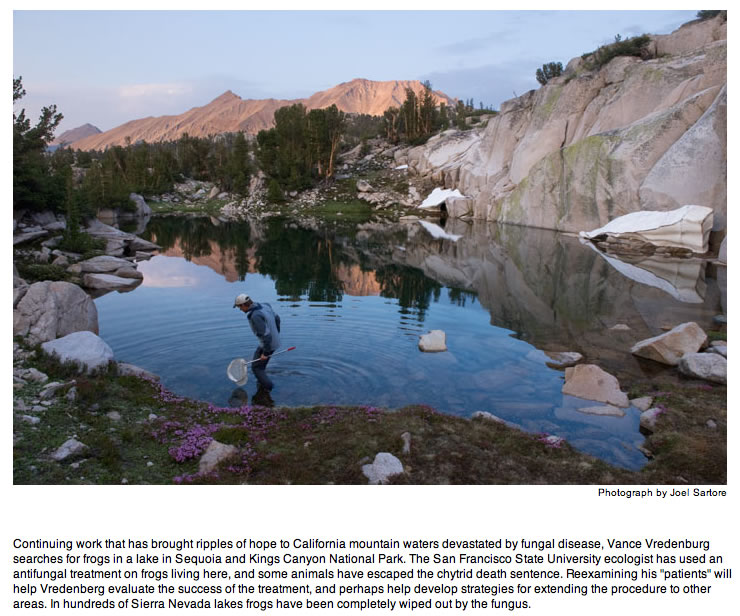

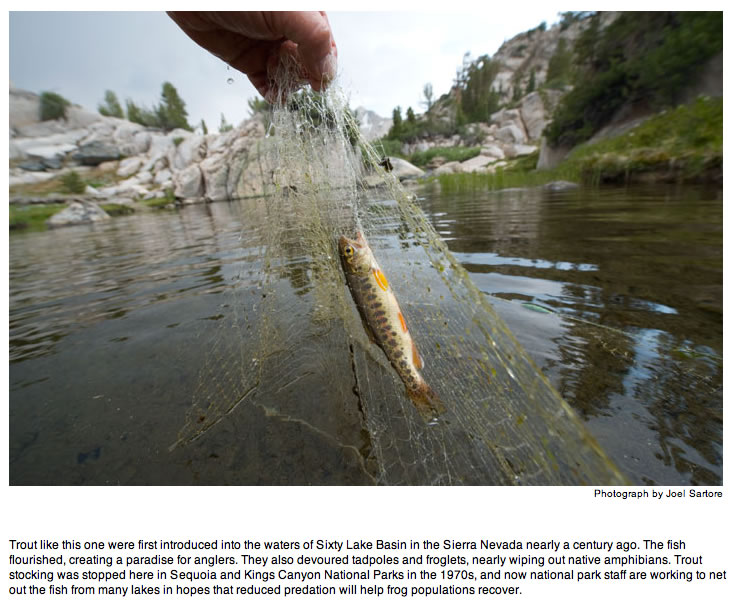

The tropics, where conditions foster high amphibian biodiversity,have seen the most dramatic declines. But more temperate climateshaven't been spared. Consider the cold, upper reaches of the SierraNevada of California. Here, at 11,000-foot-high Sixty Lake Basin,stands a stark paradise of granite towers made famous through the lensof Ansel Adams, where alpine lakes once roiled in summer with heartyfrog populations. The most common species is the mountain yellow-leggedfrog - subtly pretty, tinged yellow on torso and limbs, spotted brown andblack. But recently this palm-size frog has been hard to find.

A slender man with a camper's stubble and a soft demeanor squats atthe side of pond number 100, bordered by stoic rock walls and edgedwith pink mountain heather and tangled grasses. Vance Vredenburg is abiologist at San Francisco State University, and he's been studying themountain yellow-legged frog for 13 years, slumming in a tent on themountainside for weeks at a time as he monitors 80 different studylakes. Today, mosquito net balled up around his neck, he contemplatesten dead frogs, stiff-legged, white bellies going soft in the sun.

"It wasn't long ago when you walked along the bank of this pond," herecalls, "a frog leapt at every other step. You'd see hundreds of themalive and well, soaking in the sun in a writhing mass." But in 2005,when the biologist hiked up to his camp anticipating another season oflong-term studies, "there were dead frogs everywhere. Frogs I'd beenworking with for years, that I'd tagged and followed through theirlives, all dead. I sat down on the ground and cried."

Vredenburg's biggest remaining study population, in pond number 8,has about 35 adults. Most of the rest of the animals he's known in thisplace are gone. What happened here is the perfect example of thosemultiple punches - a case study of how a thriving species can get knockedto its knees.

It started with the trout.

Until the late 19th century, the Sierra Nevada was mostly fishlessabove the waterfalls. But state policy of fish stocking eventuallyclimbed to the high Sierra to transform those "barren" lakes into afisherman's paradise. The California Department of Fish and Game begansending trout up the cliffs, first in barrels on muleback, and by the1950s in the bellies of airplanes. (The planes would fly over the waterand let drop their living cargo, much of which missed its mark and wasleft flopping on dry land.) All told, more than 17,000 mountain lakeswere stocked.

As it turns out, trout eat tadpoles and young frogs. As trout multiplied, frogs disappeared.

Vredenburg's work in Sixty Lake Basin became an attempt to restorethe lakes to their pre-1900s fishless status in order to bring back thefrogs. He unfurled wide nets bank to bank, reeled them in, and disposedof the catch (often on the grill with a little salt and pepper).Eventually the National Park Service took over the project, and now 14lakes are fish-free or virtually so. As more fish were netted out,Vredenburg says, the "frogs started to recolonize; the lakes werecoming back to life."

But then came another blow. Chytrid, which had already invadedYosemite National Park, arrived in Sixty Lake Basin and swept from laketo lake, around a hundred of them, in a predictable and deadly line.After removing fish and restoring habitat, "to have this disease wipethe frogs out again–it breaks my heart," he says.

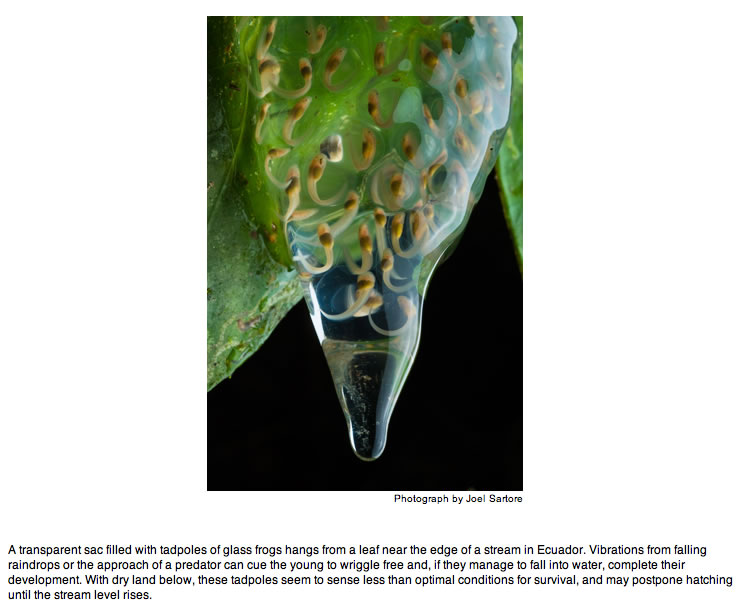

Oddly, the fungus infects but doesn't kill tadpoles, which is whywriggling schools remain in otherwise lifeless ponds. Mountainyellow-legged frogs take some six years to mature. "Those tadpoles arefrom years ago - there's been no breeding in this pond since chytridarrived," Vredenburg explains. "As soon as they transform into frogs,they'll die."

Yet Vredenburg remains doggedly optimistic. He calls pond number 8his victory pond. When he saw the frogs start to die, he removed someof the adults and treated them with an antifungal medication, then putthem back. The population - though tiny - has now been stable for threeyears running. Vredenburg plans to apply his painstakingcapture-treat-release method to animals in other ponds in Sixty LakeBasin. (Recently announced, a similar treatment project by a U.K. teamaims to mitigate disease in the Mallorcan midwife toad of Spain.) Ifenough fungal spores can be cleared from frogs' bodies, he says, thedisease may lose its hold.

Other sites are also yielding good news. Some amphibians aren'taffected by the fungus or can carry it without being hobbled. CertainCosta Rican tree frogs have skin pigments that allow them to bask inthe sun without drying out, killing the fungus with heat. Mostencouraging, Reid Harris of James Madison University and colleagueshave found an innate defense in salamanders and some frogs: symbioticskin bacteria that inhibit chytrid infection. (Some naturally occurringskin proteins show similar fungus-fighting properties.) "If we canaugment the good bacteria to help lower transmission, there may be timefor the animals to ramp up their own immunity," Harris says. "And wewouldn't be putting anything into the environment that isn't alreadythere. Perhaps we can stop the epidemic outbreaks of chytrid."

Upcoming Amphibian Ark projects may help researchers test thesemeasures. In Panama, chytrid has only recently jumped the canal andbegun a march eastward toward the still pristine Darien Province, whereat least 121 amphibian species are known. One rescue facility isalready up and running there; U.S. and Panamanian partners are nowplanning another - in part for research into how to boost enoughhealthful skin microbes in wild populations to stop the fungus cold. Ifthe strategy works, the golden frog, for one, may be returned inhealthy numbers to Panama's forests. Meanwhile, in frog-rich Ecuador,Coloma and Ron have petitioned the government for an environmentalaudit of the Limon road project. Construction has ceased for now, andsome habitat restoration may be done. Though perhaps too late to savethe choked stream's animals, media attention there could help futureland preservation efforts.

Why care about frogs? "I could give you a thousand reasons," saysColoma. Because their skin acts not only as a protective barrier butalso as a lung and a kidney, they can provide an early warning ofpollutants. Their insect prey carries human pathogens, so frogs are anally against disease. They serve as food for snakes, birds, evenhumans, playing a key role in both freshwater and terrestrialecosystems. "There are places where the biomass of amphibians was oncehigher than all other vertebrates combined," says David Wake. "How canyou take that out of the ecosystem without changing it in a major way?There will be ecological consequences that we haven't yet grasped."

"The story is much bigger than frogs," says Vredenburg. "It's aboutemerging disease and about predicting, coping with, and fighting thingswe don't fully understand. It's about all of us. Everyone should care.

Click HERE for more photos of unique Amphibians