When toads collide

Researchers want to know whether development is forcing twodesert species to cross-breed

Sunday, August2, 2009 3:28 AM

By Erin Dostal

THE COLUMBUS DISPATCH

FINDLAY, Ohio -- There are some things you just don't sendin the mail. That's why Terry Schwaner drove from Findlay to Phoenix topick up a cooler filled with 400 frozen toad toes.

That's right, toad toes.

Schwaner and his wife, Lila, even made a stop in Las Vegason the way home. They kept the specimens in their motel room, packed in dry icethey picked up at an ice-cream shop. Of course, it being Vegas, nobody asked any questions. "If you've got a cooler, they assume you've got soda orsomething else in it," said Schwaner, a University of Findlay researcher. All of this begs the question: Why drive 30 hours to thedesert for frozen amphibian parts? Nothing less than the possible extinction oftwo species.

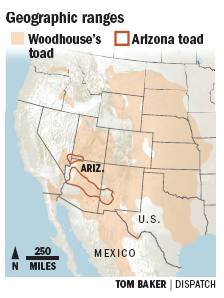

The specimens that Schwaner carried back from Phoenix willallow the herpetologist to conduct DNA analysis of Woodhouse's toad and theArizona toad. The two species have been cross-breeding for a number ofyears, and researchers believe humans are to blame. Encroachment on the toads' separate habitats -- dams,condos, golf courses, etc. -- are creating artificial opportunities for the twospecies to mingle and mate.

Random hybridization in the wild is rare. That's why expertsbelieve this case is influenced by humans. Brian Sullivan, a professor of natural sciences at ArizonaState University and a co-researcher on the project, said the Arizona toad isless resilient to drought and interference. On the other hand, Woodhouse's toad is considered a "garbage toad" that is able to live under a variety of conditions.

Experts believe that if cross-breeding continues, the Arizonatoad could disappear. "We mucked things up and caused the hybridizing,"Sullivan said. "If we want to protect the Arizona toad, we need to knowwhat we did that caused this." Turns out these little toads (these two toads, like others,are species of frogs ) also are throwing traditional ecological definitionsinto a tailspin. The old definition of "species" was that animalscould not create offspring with each other, Sullivan said. DNA research, alongwith new studies on mating practices, changed that. Usually, such as with mules or ligers (tigers and lions),the mixed offspring cannot reproduce.

These toads can.

"It's like black and white making gray," Schwanersaid. In this case, gray is bad because the Arizona toad couldpass along weaker traits to the Woodhouse's toad, sapping its resilience. Schwaner started researching the two toads in Utah's VirginRiver in the late 1990s. It was around the same time that he reached out toSullivan, who was conducting similar studies in Arizona's Agua Fria River. The two collaborated for years and published researchpapers. Despite their collaborations, the two had never met in person untilSchwaner drove to Phoenix in May. The researchers spent two days going out to swampy siteswhere the toads mate.

Sullivan looks at appearances and listens to mating calls todetermine toad species. He uses a 12-point scale that measures four physicalfeatures, including stripes and spots. Schwaner, on the other hand, uses DNA to determine whetherhe's got an Arizona, Woodhouse's or a hybrid toad. Using the combination of methods, the two hope to determinethe extent and location of hybridization. Juan L. Bouzat, a biological sciences professor at BowlingGreen State University and a colleague of Schwaner's, said this kind ofresearch is important for developing conservation methods.

"There is a drastic decline in amphibian populationsthroughout the world as a result of human activities," he said. "Thistype of research allows us to understand the processes that driveextinction." Researchers are investigating troubling deformities anddramatic population declines afflicting frog species around the world.

Some researchers see frogs as an "indicatorspecies" for water-pollution problems that could threaten humans. But back to the cooler full of toes. Why just a digit? Using just the toes is part of the conservation plan,Schwaner said. In the past, large amounts of tissue were needed for DNAanalysis. That meant removing livers and hearts. Now, a toe will do. And that lets the toad survive.

Jessica Claudio, an intern of Schwaner's, conducts much ofthe lab work at the University of Findlay. She said the toads tell an importantstory. "People will become more aware about how we affect theenvironment," Claudio said. "It's an area that really needshelp."

Arizona Toad

Woodhouse's Toad

Woodhouse X Arizona Toad Hybrid Mix